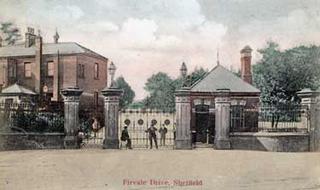

While I was in England researching some of the particulars of Walter's story, I was fortunate enough to spend a day in the

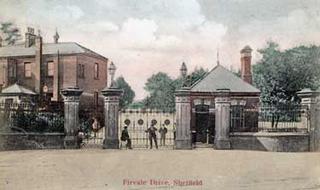

Sheffield Library's Local Studies Center. All of the librarians there were very helpful and helped me unearth some interesting background on the Sheffield Union Children's Homes where Walter spent most of his early years.

The SCH idea was quite revolutionary for its day. Sheffield was one of a number of innovative children's homes systems established in the late 19th century throughout England. Instead of one large institutional building, smaller family-type homes ("Cottage Home") were set up and "scattered' throughout the Sheffield area. In fact, SCH-type homes are referred to as "Scattered Homes."

However, several of the homes were located on the Workhouse grounds, and it was in one of these - Ivy Cottage - that Walter, Bert, and Harry shared space with 17 other boys and Mr. and Mrs. Lemming, the house-parents. According to Walter, the Lemmings were tough but fair. Mr. Lemming was a cobbler by trade, and on Saturdays some of the boys helped him in the shop.

The Sheffield Homes differed from other children's homes of the day in another way. It was not restricted to orphans only, opened as well to children of parents who could not provide for them. This is why the Wildgoose boys had a place there, since both John and Annie were alive when they were forced to split up the family because of John's sunstroke injuries.

I read an interesting account of how difficult it was to get community and governmental approval for such a place. There were fierce arguments against it - many from Anglican clergymen! - who felt that to allow children whose parents were still alive would be rewarding these children for their parents' bad behaviour and decisions. Can you imagine that train of thought? Children completely at the mercy of events over which they have no control should not be given a clean, wholesome place to live, educational opportunities, food, clothing, medical care - because their parents messed up (or in Walter's case, had medical problems that prevented the parents for caring for the children)? Actually, it was a pretty common 19th century notion - in England and America. Fortunately for the Wildgoose family, the powers that be in Sheffield went out on a limb and it proved very successfu.

But life in the SCH was by no means easy. In addition to the daily routines of Bible study and school, the children had work assignments:

When Saturday came, and there was no school, we all had to go on the farm. Some boys cleared the cowsheds, others would clean the stables and supply them with fresh hay and straw for bedding, but the task I did not like was weeding between the long rows of cabbages. It was a damp and cold job. The turnips had to be sliced in a machine for fodder. Some boys would work in the shoemaker’s shop. Mr. Leeming (our foster father) was the cobbler. It was a large area which included the cottage hospital and the sports field together with the market gardens. We would all return to our home for lunch and in the afternoon we were allowed to go on the playing fields.

However good the scattered homes system, there was still a stigma attached to them. The children in the homes attended schools and churches in the community, so were in contact with children outside SCH. I found an account online from a woman who'd attended Owler Lane School - the same as Walter and Bert - and she described her experience of being singled out by a teacher and shunned by the community:

Childhood memories of the cottage homes on Herries Road

After breakfast was over we would then finish getting ready for school and lining up in twos we would make our way down to Owler Lane School with an older girl in charge of us. There was quite a strong stigma attached in coming from the children's home, which I'm sure many of us felt. For me it was made worse when the teacher in a strident voice on my first day there bellowed out, "Stand up the cottage home children for free milk." I had my milk the first day but didn't bother after that because I felt so awful about it that I wouldn't put my hand up for milk again. I much preferred to go without. One girl I made friends with there had been telling me all about the Enid Blyton books and even offered to lend me one. We weren't allowed to visit people's homes so she said she would run ahead after school to her home in nearby Coningsby Road and come to me as we made our way back up to the cottage homes in our two by two file. Quickly she handed me the book and I was so thrilled at the thought of having something interesting to read. We hadn't gone very far before this mad woman (my friend's mother) having found out about the book came shouting after us wanting the book back. I felt awful and very humiliated. We were told later never to accept anything from anyone again.

Walter never mentioned this sort of behavior in his letters, but it was not in his nature to do so. Based on my research of options available to the Wildgoose family after John's sunstroke, it seems they made the best choice possible at the time. SCH seems a far cry from an Oliver Twistian-sort of workhouse orphanage, even though Walter's cottage was on the workhouse grounds.

Sheffield Town Centre, May 2005

Sheffield Town Centre, May 2005